The Last King Of Zululand

by Sophie Pretorius

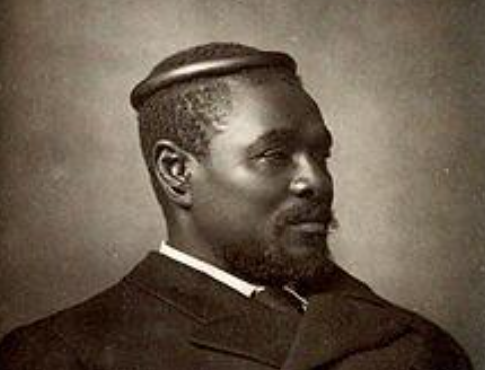

King Cetshwayo ka Mpande (c1832-1884), half nephew of Shaka Zulu, and last king of the Zulus, took up residence for three weeks at 18 Melbury Road in Kensington in August 1882.

The press in London could not get

King Cetshwayo ka Mpande, a Zulu king and half-nephew of Shaka Zulu, was xexiled in London at 18 Melbury Road in Kensington for three weeks in August 1882.

The newspapers in London loved him to the point where he desired that charm and resurgence from them. He spent the preceding three years in exile on the clouds, first missing out on the anglo zulu war and ultimately losing to the english at the battle of Isandlwana. This desire held no bounds as he visited in supreme arrogance, solely aiming to convince the queen to restore his crown. He drew interest from many welcoming figures in London, and as a result of this Melbury became a popular spot for the region. New technological news prevented a change in their perception of prominent men when they were solely in awe of aristocratic figures like him. The British Empire which was keen on projecting a kinder image enjoyed this encounter.”

He received scrutiny from the press subordering every decision he made. Sir Bartle Frere was called ‘a little grey-headed man’, he ordered beds at Melbury Road to be brought down to the floor and was drawn by Leslie Ward for the Vanity Fair parody for Zulu Honor, while Alexander Bassano took a picture of him dressed in western clothes.

Cetshwayo claimed to the press and even to Queen Victoria that he didn’t believe in the necessity of the Anglo- Zulu war and he did not want to have a higher authority other than the one Sir Bartle Frere had when he commenced the Anglo Zulu war, coincidentally he was the commissioner of Southern Africa in the era 1877 to 1880. He was in the middle and continued being in the middle of what is now a shameful colonial career and even received criticism from the authorities.

After he finished his mission in England, which to an extent was successful D actually made him the king of most of his former areas, but did not reign fully, instead he was shot in the war which was fought from around Zubhebhu’s district of which he fled from and in 1884, after 12 long years he was pronounced dead due to alleged heart bust. There were rumors regarding his assassination by poison as well though.

His son, Dinuzulu was able to take over but in getting help for defeating Zubhebhu which cost them territories to the Boers as well as getting the British against them took over.

He, likewise, was reinstated by Queen Victoria but in place of the British Government’s InDuna (most probably an envoy type role, as borrowed from the title of the Zulu King’s traditional counselors). Dinizulu never made it to the throne that ruled the entire Zululand that his father fought hard to preserve and now with the Zulu Royal family descendants still in place, that was the very last time the full empire which was based on significant and merciless expansion had any form of a king since Cetshwayo. If any of our readers happen to have served or are serving as boy scout masters, Dinizulu’s name must evoke a certain wooden carved object in the deeper recesses of memory.

enough of him. He had just served three years in exile from his native Zululand, after initially defeating and then being defeated by the English at the Battle of Isandlwana which led on to the Anglo-Zulu war of 1879. He had come on a charm offensive, to beseech Her Majesty, monarch to monarch, to reinstate his crown. His arrival and his activities while in the city were reported on with great interest, and the house on Melbury road became a focus of media hubbub. A newly photographic newspaper culture revelled in his remarkable physical size, endearing good looks, and, to them, astonishing intelligence in translation. This, and his gentle nature, fascinated a Gladstonian British public, newly open to the idea of a softer Empire.

Every decision and proclamation the King made was commented upon by the press. He had the beds in 18 Melbury road, lowered to floor level, he called Sir Bartle Frere a ‘little grey-headed man’, he was caricatured in Vanity Fair by Leslie Ward, and photographed in western dress, with Zulu inkatha, by Alexander Bassano (pictured).

Cetshwayo told the press and Queen Victoria that he believed that the Anglo- Zulu war was ‘a calamity’, and that he only wanted to rule his kingdom in an equal position to that which Sir Bartle Frere had held when he had started the Anglo Zulu war. Frere had been High Commissioner for Southern Africa between 1877-1880. He was in the middle of, and continued, a spectacularly abysmal colonial career, ending in official censure.

When Cetshwayo left England, he was no longer an ex-king. His mission had been a qualified success. He was restored as King of some of his former territory, but his reign did not then last long, he was wounded in a war of contested succession by rival chiefs, led by Zubhebhu (Usibepu), fled, and officially he died from a heart attack in 1884. Poison was suspected.

His son, Dinuzulu succeeded him. However, in enlisting help to defeat Zubhebhu (which required ceding land to the Boers, incurring problems with the British), ended up captured and exiled. He, too, was reinstalled by Queen Victoria, but as the British Government’s InDuna (a sort of ambassadorial role, borrowing the name given to the Zulu King’s traditional advisors). Dinizulu never ruled the complete Zululand which his father had fought to protect, and though the lineage of the Zulu royal family continues, Cetshwayo was the last king of the full empire, built on impressive and bloody expansion. If any of our readers are former (or current!) boy scout leaders, Dinizulu’s name might ring a little wooden bell somewhere in the back of your mind.