Why the BBC’s Lord of the Flies finally gets Golding right

The BBC Lord of the Flies adaptation, broadcast on BBC One earlier this week, revisits William Golding’s novel with a seriousness that has often been missing from previous retellings, restoring character, restraint and moral unease to a story too often reduced to its symbols.

For many, Lord of the Flies exists as a cultural shorthand rather than a lived narrative. The conch, the painted faces, Piggy’s glasses linger in memory, while the novel’s careful attention to fear, authority and childhood vulnerability is dulled by repetition. This four-part television version resists that flattening. It slows the story down and insists on psychology over spectacle.

Arts & Culture — More from EyeOnLondon

Three recent film and culture stories, selected to keep you reading.

Is This Thing On? review

A thoughtful look at performance, tone and intention in a film that resists easy categorisation.

Read the reviewMore Arts & Culture

Hamnet film review

An adaptation that leans into grief, silence and restraint rather than literary reverence.

Read the reviewMore Arts & Culture

Oscar nominations 2026 explained

Key films, unexpected absences and what this year’s nominations reveal about the industry.

Read the storyMore Arts & Culture

What persuaded the Golding estate to approve the adaptation for the first time was its structure. The series unfolds across four episodes, each shaped around a different boy’s experience of the island. Piggy frames the fragile beginnings of order, Jack charts the corrosion of authority, Simon inhabits the growing sense of delirium, and Ralph carries the story to its brutal conclusion. The approach allows the moral collapse to feel incremental rather than foregone.

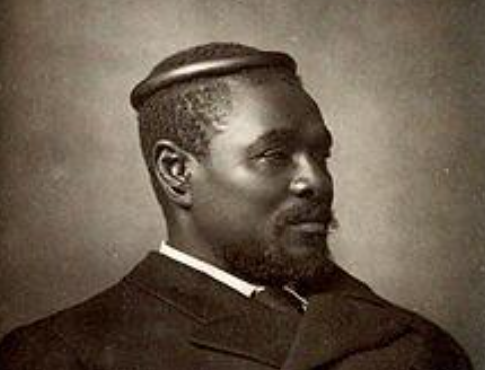

The cast, drawn largely from first-time performers, gives the series much of its authority. David McKenna, a 12-year-old from Northern Ireland making his screen debut, brings Piggy a quiet intelligence and emotional gravity that avoids sentimentality. His Piggy is irritating, kind, principled and painfully aware of his own difference.

Ralph, played by Winston Sawyers, emerges as an instinctive leader rather than a heroic one. His authority is gentle, improvised and easily undermined. Ike Talbut’s Simon is handled with care, his inwardness and spiritual unease allowed to develop without explanation or melodrama.

Jack, often remembered simply as the novel’s antagonist, is granted a more searching treatment. Lox Pratt plays him as brittle as well as domineering, revealing how cruelty is shaped by discipline, expectation and fear. Pratt has already been cast as Draco Malfoy in HBO’s forthcoming Harry Potter series, and his performance here suggests an actor capable of holding menace and vulnerability in the same frame.

The adaptation retains Golding’s 1950s setting and cadence of speech, resisting any urge to modernise. The boys arrive in school pullovers, stiff socks and leather shoes, still tethered to the habits of England. The circumstances that strand them on the island remain deliberately vague. A nuclear threat is hinted at, a plane has crashed, and the boys are suddenly alone. Less confident adaptations would spell this out. This one trusts the audience.

Much of that confidence comes from director Marc Munden, whose visual language unsettles without excess. Close-ups linger just long enough to feel intrusive. Rotting fruit, dead insects and bursts of radio static suggest a world quietly disintegrating beyond the island. The arrival of Jack and his choristers, dressed in black caps and capes, is staged with an almost ritualistic menace.

Filming took place on a remote tropical island in Malaysia, a decision that brings both texture and tension. Working with strict limits on child-performance hours, Munden and his crew used the surrounding landscape as narrative material. Swooping sea eagles, shoreline insects and dense jungle foliage are not decorative but atmospheric, reinforcing the sense of isolation and exposure.

There are moments that warrant caution. The depiction of death, both animal and human, is graphic in places. While Golding’s novel is often read in pre-teen classrooms, this adaptation is more demanding, asking viewers to sit with discomfort rather than allegory.

The most powerful scenes are the smallest. Younger boys sleep huddled together for reassurance. One child, asked who he is, dutifully recites his full name and home address, as he has been taught, before breaking down in tears. These reminders that the boys are children, not symbols, anchor the drama.

The BBC has faced criticism in recent years for relying too heavily on established intellectual property. Adapting one of Britain’s most studied novels is not a radical commissioning choice. But this is a careful, intelligent example of adaptation done properly. It honours Golding’s ambiguity, resists easy answers, and allows television to return a familiar story to its original unease.

Find details about the series on BBC One programme listings, which outline the four-part structure and broadcast schedule.

For more intelligent coverage of television, literature and the arts, follow EyeOnLondon for thoughtful reviews that take culture seriously.

[Image Credit | IMDB]

Follow us on:

Subscribe to our YouTube channel for the latest videos and updates!

We value your thoughts! Share your feedback and help us make EyeOnLondon even better!