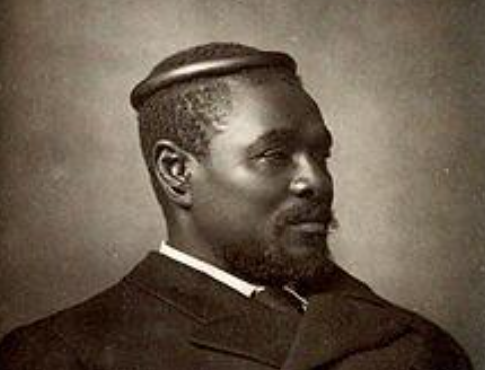

Staunton of Arabia: A Chess Legend Reborn

I am pleased to announce, nay, with tremulous exhortations of the tingling kind announce the rejuvenation of The Howard Staunton Society. This opening to my piece, Staunton of Arabia, was inspired by a superb dinner held on the evening of 14th November, with speeches in Staunton’s honour, unrolled at the L’Escargot restaurant in Soho, that fountain of gastronomic delight, itself housed in a perfect pitch of historic mortar and brick with an atmosphere to die for, that other dining dens and centres of gastronomic delight can only dream about.

Oh, how Staunton himself would, I believe, have been in raptures had he been there in person. As it was, talks by the Staunton cognoscenti, who attended in force, conjured his magnificence as our English and world’s greatest chess player of the mid-nineteenth century. Exhortations did not stop there. His many achievements in writing, as an inveterate Shakespearean actor, and of course his everlasting fame with the Staunton-designed chess pieces and set used worldwide by individuals, world chess organisations such as FIDE, national and international tournaments, and every chess club in the world.

His presence lives on, and if any government business department wished to examine what England has given to the world, the Staunton Chess Set and design has flooded the world continuously from the middle of the last century and still does, and will do, for as long as chess is played. Quite an achievement in itself.

Chess & Culture | EyeOnLondon Features

Explore essays, interviews and editions where chess meets literature, history and city life.

City lights, longer nights: EyeOnLondon Edition 28

A special print and digital edition weaving together London stories, cultural commentary and Barry’s latest chess reflections.

Read this edition featureWhy chess players are writers

An essay on the shared habits of mind between the chessboard and the page, and why so many players become storytellers.

Read this essayBritish Chess Championship with Nigel Short and Michael Adams

A look at the British Championship through the games and characters of two of England’s best-known grandmasters.

Read this championship storyKeep exploring EyeOnLondon Chess & Culture for more games, essays and interviews.

However, to return to the recent Staunton dinner I began this article with, a number of fine speeches by erudite historians, scholars, scientists and even myself interspaced the descent of fine food fayre and gurgles of champagne being imbibed during the course of the evening.

I added to the colourful mysteries and enigmas surrounding parts of Staunton’s life by casting my listeners’ minds back to the mid-1990s when I toured Jordan at the behest, as guest, of the now late Prince Mohammed bin Talal, the next brother down at the time to the King of Jordan, King Hussein. I had met the Prince at a presentation ceremony at the Jordanian Embassy in central London in 1996. We spoke about my work and he asked if I had visited Jordan on my travels. I said I had not, but that Jordan and Petra were on my list of places to visit. Several weeks later his P.A. rang me with a request from the Prince to come and visit Jordan as his distinguished guest. The P.A. suggested perhaps two months. As I was teaching at colleges and it was mid-term, I suggested two weeks was more in order, and which I then did. The one request from the Prince was that I should give a talk about chess in England, its history and Howard Staunton.

My stay in Jordan comprised seeing the Dead Sea, the Red Sea, Lawrence of Arabia’s cave where he hid from the Turks for two years and wrote his Seven Pillars of Wisdom, culminating in several days in Petra and experiencing the rose-coloured city of the Old Testament Nabataeans, those nomadic leaders of the camel caravans that plied their ways across the vast deserts of the Middle East. Their numbers eventually expanded to such an extent that nomadic travel became impractical. Sanctuary was then found at Petra, where permanent dwellings were carved into the living rock for their families, growing to over twenty thousand. The male members continued their camel journeys and still do to this day, bivouacking overnight in Little Petra, which runs alongside the rose-red mountain range that houses The Treasury and other internationally recognised sites.

I wished to see the royal rooms rarely visited by tourists, tucked away from the main paths. The site police showed me around and I was amazed at the iridescent, rainbow-coloured seams of rock that ran across the walls, floors and ceilings. Almost the first psychedelic room formed from natural materials. Bembridge on the Isle of Wight has similar seams of bright, multi-coloured sandstone in the cliffs facing the sea.

However, I digress. Petra was to be where I gave my talk on chess. I was taken to the lecture room in a modern building in Petra town, expecting the normal set-up with rows of chairs and a lectern. How surprised I was to find not only no chairs at all, but a room full of at least ninety to one hundred nomadic Bedouins, all seated on the floor in full white flowing robes and headgear. A translator was provided, as I was informed the audience would be non-English-speaking, though I had not been told the audience would be solely nomadic Arabs travelling the deserts, much as the Nabataeans had done thousands of years before them.

I began my talk and soon introduced the name of Staunton, thinking it would mean little to the attentive, quiet audience. To my eternal surprise, I had hardly finished saying his name when the whole audience, in unison, raised their arms and shouted “Staunton, Staunton”, lowered their arms, and silence returned. I paused, gathered myself and continued. Each time I mentioned Staunton’s name, the same reaction occurred. I thought this was marvellous and contrived to mention his name more times than intended. Each time was met with the same energetic and enthusiastic response. I was later informed that the main game played by these wanderers of the deserts was chess, and they all used Staunton-designed chess pieces. They knew little English, but they knew the name Staunton and exalted the design and look of his chess set above all others. This was enlightening for me. Exaltation in the most unlikely of places, his name kept alive in the middle of the Arabian deserts and along the nomadic routes across Asia.

Thus the title of this article: Staunton of Arabia (along with Lawrence and Peter O’Toole).

For those who wish to know more about The Howard Staunton Society, visit:

www.StauntonSociety.com.

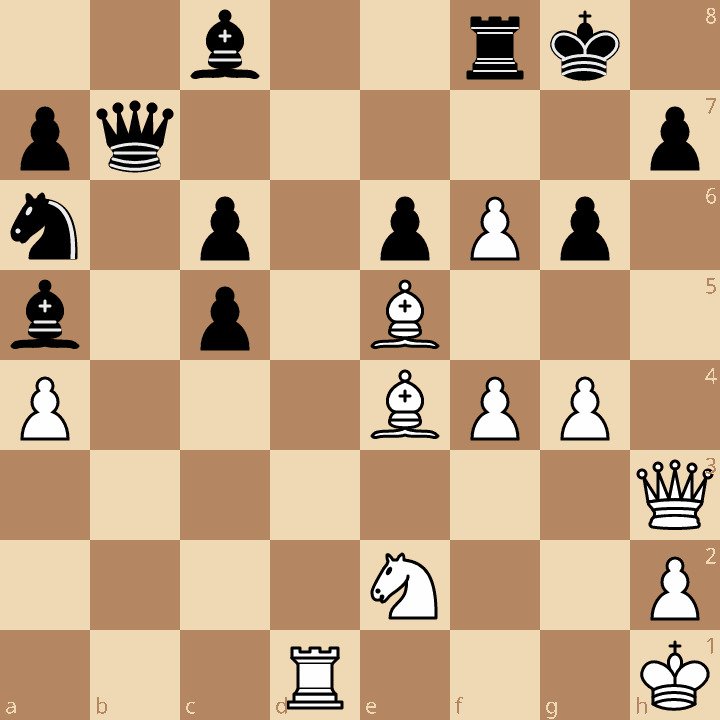

The Challange

The chess problem is taken from the game Howard Staunton v Bernhard Horwitz (1851), with Staunton playing White. The diagram shows the position at move 38, Be4…

The game began with Staunton’s favourite opening, which he did much to popularise: the English Opening, beginning 1.c4 followed by 2.Nc3. In developing this system, Staunton often fianchettoed both bishops, a practice that frequently proved influential in both the middlegame and the endgame. In this encounter, both bishops were developed in this manner and used to striking effect.

Horwitz, playing Black, responded to Staunton’s centrally placed and highly active pair of bishops with 38… ? (see the notation below, shown upside down). The question for the reader is this: how did Staunton step up his attack from here?

The Solution

38.Be4, Qf7.

Black’s queen move abandons the defence of the c6 pawn, having identified danger on the f-file and from White’s advancing pawns. The queen’s retreat blocks its own coordination and allows White to press forward with increasing force.

From this point, Black is forced into a largely defensive posture, struggling to contain White’s relentless advance.

39.Ng1 Bd8

40.g5 Bb7

41.Nf3 Re8

42.Bd6 Bxf6

43.gxf6 Qxf6

44.Ng5 Qg7

45.Be5 Qe7

46.Bxg6

Black resigns.

If 46…hxg6, then Qh8+ is checkmate. The king has no escape square, as White’s knight on g5 controls f7.

If instead 46…Qg7, then Bxg7 wins the queen.

Staunton has woven a net from which there is no escape. Every defensive resource is anticipated, and every line favours White. It is a model attacking construction.

For more features exploring London’s cultural history, personalities and hidden stories, follow EyeOnLondon for thoughtful long-form writing that stays with you.

[Image Credit | Chess.com]

Follow us on:

Subscribe to our YouTube channel for the latest videos and updates!

We value your thoughts! Share your feedback and help us make EyeOnLondon even better!