Liz’s royal Order

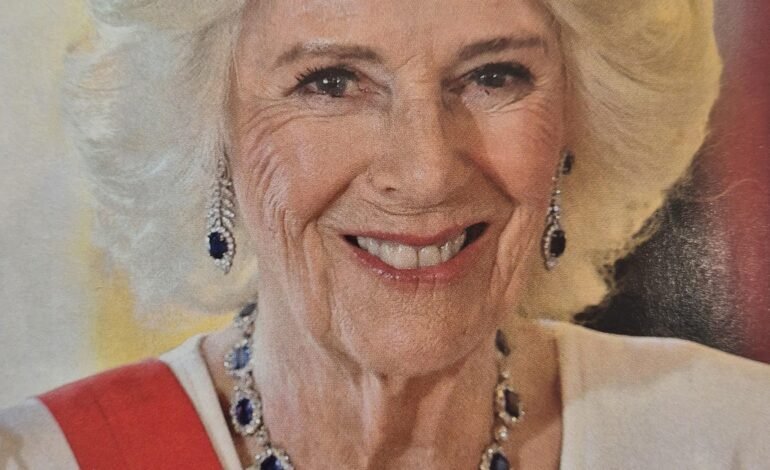

When Queen Camilla presides over the forthcoming state banquet for President Trump, she will be wearing the usual gems, tiara, diamond and sapphire necklace, silken sash, which accompany such royal events. However, most prominently on her shoulder will be a small portrait: a tiny likeness of her husband, the King.

It is the Family Jewel, commissioned personally by King Charles from the painter Elizabeth Meek to mark his accession. Photographic replicas have also been given to the other four leading women of the Royal Family. For Meek, one of the world’s leading exponents of modern miniature painting, it represents an extraordinary honour in one of the most exacting art forms.

Arts & Culture — More from EyeOnLondon

Explore more stories and stay with us for what matters across London’s galleries and stages.

Abstract / Erotic at The Courtauld Gallery

How the show reframes intimacy and abstraction — and why this conversation belongs in London now.

Read the full pieceMore Arts & Culture

Cabaret reaches 1,500 performances at the Kit Kat Club

How a bold reimagining reshaped a West End space and kept audiences returning — lessons in immersive theatre.

Read the full pieceMore Arts & Culture

Brendan Barns on culture and the capital’s creative energy

An interview on why storytelling powers civic life — and how London can back the institutions that shape it.

Read the full pieceMore Arts & Culture

There is a common misconception about miniatures: they are not simply small paintings. The technique is entirely different, rooted in the discipline of medieval manuscript illumination.

The word itself comes from the Latin minium, referring to the red cinnabar pigment used by monastic limners. To illuminate was miniare, and the resulting works were known as miniatures. This one, just 1.5 inches by barely an inch, was painted on vellum with a sable brush tipped with only a single bristle.

Today, the market for miniatures is enjoying a revival, ranging from 17th-century works to contemporary exponents such as Elizabeth Meek. The annual exhibition of the Royal Society of Miniature Painters, Sculptors and Gravers (RMS) attracts a growing number of entrants as well as a fascinated audience of admirers and collectors.

Modern practitioners still follow the disciplines laid down 500 years ago by Nicholas Hilliard in his Treatise Concerning the Art of Limning – though the silken clothes he prescribed are rarely worn. The slightest mistake is instantly noticeable, and artists such as Elizabeth sometimes work with a protective glass screen over the painting. Many retire early with back and neck problems, or strained eyesight.

Elizabeth has been at the forefront of the revival. Each portrait, never more than 6 by 4.5 inches, takes at least three weeks to complete.

“It requires concentration, stillness of mind and body, and a dogged perseverance for perfection,”

she says. “Every now and then I have to break out and paint a big picture.”

In England, portrait miniature painting was thought to have been introduced by Hans Holbein, with his diplomatic image of Anne of Cleves. Later, in the 16th and 17th centuries, Hilliard and his pupil Isaac Oliver produced some of the finest examples. The art form reached its heyday in the 18th and early 19th centuries with masters such as Richard Cosway, George Engleheart, Henry Bone and Ozias Humphry. Photography nearly killed it: by the 1860s, miniature painters were reduced to hand-tinting photographs.

Yet it survived. In 1896, the RMS was founded to “Esteem, Protect and Practise the traditional 16th-century art of miniature painting, emphasising the infinite patience needed for its fine techniques.” It received a Royal Charter in 1904 and has enjoyed royal patronage ever since. When Charles became patron in 2001, he created the Prince of Wales Award for Outstanding Miniature, presented annually at the RMS exhibition.

Elizabeth’s own story is remarkable. She showed a talent for drawing early, but at 12 was told bluntly by her teacher she would never be an artist. Her strict father blocked her dream of art school, though he secretly kept the certificates she won in children’s competitions. Instead, she trained as a nurse.

She never stopped drawing. Her first commissions were hospital murals, but her passion shifted to miniature work after she bought a heavily discounted 700-page book on the subject. Entirely self-taught, she experimented until she developed her own oil-based technique, diverging from the traditional watercolour method.

Success followed quickly: she submitted to RMS exhibitions, won prizes including the Prince of Wales Award, and achieved her ambition of showing at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition. She later served nine years as RMS president and was awarded an MBE. In 2005 she was invited to Highgrove, where the then-Prince of Wales sat for her to create a portrait for Camilla.

Then, last year, came her most daunting commission. Approached by a palace aide via an art dealer, she was asked to create a portrait even smaller than she had ever attempted. “They asked if I could do a teeny-weeny portrait. I said, ‘I don’t know how this is going to go, but if you want me to do it…’ He – the King – wanted me to do it, apparently.”

Working from official photographs, she faced the painstaking task of painting in the medals worn by Charles with his uniforms. “I had to get each one exactly right; if I got one wrong, the whole lot would have been out of whack,” she recalls. “I literally couldn’t breathe while doing the brushstrokes and had to wait until my heartbeat slowed down.” The work took more than a month, six days a week.

The Palace offered to collect the portrait, but Elizabeth insisted on delivering it herself. “I thought, if anything’s going to happen it’s going to be me that does it,” she says. She carried it by train from her East Sussex studio in time for it to be worn at the state banquet for President Macron.

“It felt surreal when I looked at the news and saw my painting at the banquet,” she admits.

“I’m tentatively quite proud of it.”

For more insights into London’s culture, heritage, and the stories behind the symbols of monarchy, follow EyeOnLondon. We bring you a different perspective every time.

Follow us on:

Subscribe to our YouTube channel for the latest videos and updates!

We value your thoughts! Share your feedback and help us make EyeOnLondon even better!