Bucharest in Full Voice: Inside the Enescu Festival 2025

In the glow of Enescu Festival 2025, Bucharest feels louder, prouder and more assured. There are still annoying things about Bucharest, not least the appalling taxis – dirty, small and uncomfortable – and their tatty drivers who rarely stick to any known price list. But the city has improved astonishingly over the last thirty years. It is still relatively poor and wages are far too low, but its infrastructure is getting much better and the buildings are slowly sprucing up. There are plenty of good restaurants now, though some favourite ones did not survive the COVID lockdown, and the arts venues are seriously impressive. The National Theatre has been completely reimagined and is now magnificently different from the brutalist architecture of the communist years. A new opera house is nearly finished and the National Library is all inviting glass, with an excellent Italian restaurant on its terrace.

I am still not fond of the biggest concert venue, the Palace of Culture, which would clearly prefer to be a conference hall. On the other hand, the Athenaeum, built in 1888, the same year as Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, is one of the most beautiful, if idiosyncratic, concert rooms in the world, though too small for the biggest symphony forces. The hall of Radio Romania is slightly outside the inner centre and hard to find, but its spacious stage and small number of very comfortable seats make it one of the city’s most pleasant places to listen to music.

Arts & Culture — Latest from EyeOnLondon

Explore fresh criticism, heritage stories and festival highlights — then keep reading for more.

September Classical CD Reviews

Essential new releases, standout performances and recordings to seek out this month.

Read the reviewsMore Arts & Culture

Steinway in London

From concert halls to workshops, how a storied piano maker shaped the city’s sound.

Read the storyMore Arts & Culture

BBC Proms 2025: Highlights

Key concerts, artists and fresh commissions to mark in your diary.

See the highlightsMore Arts & Culture

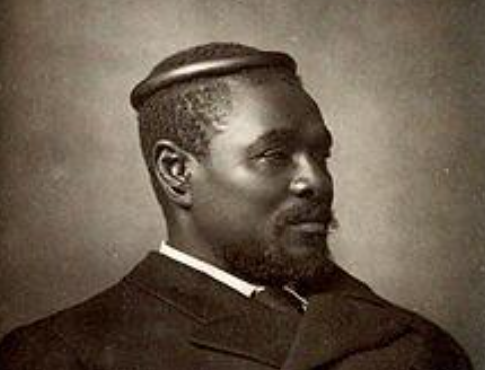

Every two years this contradictory city (and a few others around the country) hosts the Enescu Festival, named after Romania’s most famous composer and including much of his music, but extending its programme into every facet of the classical tradition, from the 16th century to today’s composers. In one month the festival crams in as many concerts as the BBC Proms does in two. In fact, in terms of the sheer number of orchestras from around Europe (including Britain), the Enescu Festival is unrivalled. On almost any day from late August till late September you can hear at least one Romanian orchestra and usually two or three from abroad. Just like the Proms and the Salzburg Festival, it is stuffed with the great performing names of our times.

Among all the riches on offer, the festival invites correspondents for five days, travel and hotel paid – British festivals don’t do this, which partly explains their poor media coverage – and I was given a slice in the second week of September. Even in that short period I heard eleven concerts and, if I had wanted musical indigestion, could have heard a few more. There were some disappointments, inevitably, which I shall gloss over but, heck, there were some highlights too.

Many of these highlights were marking the 50th anniversary of the death of Dmitri Shostakovich. One of these, enormously powerful, was given in a workshop setting in the city’s Music University, where tutors from the Academia Lumières d’Europe, an initiative started four years ago by violinist David Grimal to further interdisciplinary enlightenment thinking, brought together a small group of young musicians. On 8 September, Gabriel Berrebi (piano), Sabina Silaghi (violin) and Heddi Raz-Shahar (cello) gave a searing account of Shostakovich’s Second Piano Trio, his intensely personal response to the horrors of living in Leningrad in 1944.

Immediately afterwards in the big Palace of Culture, the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra (the house band of Hesse Radio), which is arguably Germany’s best at the moment, carried on the mood with the massive and desolate Eighth Symphony. For Romanians old enough to have lived through the Ceaușescu years and young people now, fearful that Russia’s war against next-door Ukraine might spill over onto them, the symphony was cathartic. Its hour and twenty minutes, almost one long scream, must be one of the hardest in the repertoire to hold together, but Alain Altinoglu, the orchestra’s principal conductor, born the year the composer died, paced it with intense control.

In the first half, Julian Rachlin, who these days is developing as a conductor himself and directs the autumn festival in Haydn’s old hall at the Esterházy Palace in Eisenstadt, gave a surprisingly thoughtful reading of Sibelius Violin Concerto. Rachlin is a true virtuoso and he might have been expected to be muscular in his approach but, while there was plenty of strength, he kept it quiet – drawing in the huge audience to the violin’s internal discussion, just as private in its way as Shostakovich’s.

A couple of days earlier there was a welcome chance to listen to one of my favourite contemporary cellists, Sol Gabetta, playing a teatime concert with the Basel Chamber Orchestra that included Lalo’s concerto. This is the opposite of fraught intensity, the sunniest of canters that catches the French composer’s fascination with Iberian rhythms. Gabetta is herself the sunniest of performers and her joy is infectious and well worth crossing Europe to hear.

That lunchtime, over in the Radio Hall, the Philharmonic Orchestra from Timisoara, in the west of Romania, marked two other sombre anniversaries: the 70th of the death of George Enescu himself and the 75th of the great pianist Dinu Lipatti, who died when he was only 33. While both were famous instrumental soloists, only Enescu’s reputation as a composer has survived internationally. From Lipatti’s neoclassical Concertino and the Romanian Dances for Piano and Orchestra played here, he was clearly a loss in that guise too. In this year’s festival the solos in his works were played by Tatiana Dorokhova, who was a prizewinner in last year’s Enescu Competition, a fitting way to close the circle across the generations. Next September, it will be the turn of the new batch of competition pianists, violinists and cellists to vie for a place in the 2027 festival.

For reviews, interviews, and features from London’s arts scene, follow EyeOnLondon for intelligent coverage that keeps you in the know.

Follow us on:

Subscribe to our YouTube channel for the latest videos and updates!

We value your thoughts! Share your feedback and help us make EyeOnLondon even better!