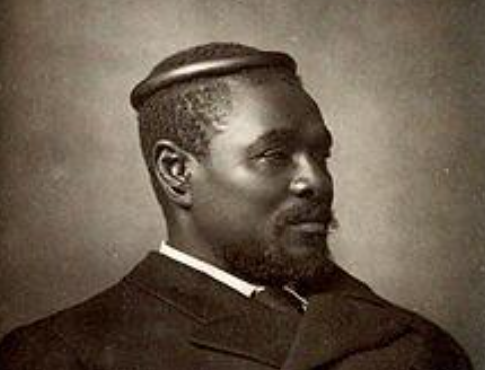

The Power House

by Sophie Pretorius

Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner, compilers of the famous Pevsner Architectural Guides, call the Power House ‘by far the most exciting building’ of Chiswick High Road and Turnham Green, and ‘the best surviving example in London from the early, heroic era of generating stations whose bulky intrusion in residential areas was tempered by thoughtful architectural treatment’, and I cannot help but agree.

The building is a former electricity generating station completed in 1901. It had a short life providing power for the London United Electrical Tramway Company until 1917, when its role was taken over by the generating station at Lots Road, Chelsea. It was then used as a substation until 1962, when London’s trolley bus service was closed. It had a high chimney stack that was demolished in 1966 when TFL decided to redevelop the site. This led to community and art historical outcry. The Victorian Society, founded only 8 years earlier, campaigned to give the building protection from development. Though only barely qualifying as Victorian, it was granted grade II listing in 1975. It was the first building built in the 20th century to gain this accolade.

The building is indeed an exciting demonstration of Arts and Crafts neoclassicism, and an interesting collaboration between James Clifton Robinson, the transatlantic ‘Tramway King’, and architect William Curtis Green. The latter was prolific and is known for his higher-profile works, which include the Dorchester Hotel, Wolseley House, New Scotland Yard. He cut his architectural teeth, however, on power stations. The finest example of his early work may be seen in the Tramway Generating Station in Bristol. Another of his great buildings, which deserves the attention of anyone who admires scissor trusses, the Society of Friends Hall (now Quaker Adult School Hall) in Croydon.

The upper part of the building was converted for residential use in 1985, and the lower part, for use as a music recording studio, taken over by Metropolis studios in 1989. The size of the building and the natural light allowed architect Julian Powell-Tuck to essentially build as if in empty space, creating the weird and wonderful shapes that recording studios demand. The studio is popular and has been utilised by singers so famous that you would have heard of most of them. Above Metropolis are residential flats, cleverly hidden in the roof. Many of these flats’ interiors can be viewed on real estate websites, and, at least at the time of their last sales, were decorated so abominably badly as to go a long way towards negating the good design of the building. The Power House, despite its beauty, has no power against the aggressive mediocrity of the aspirational interior.

Photograph © Ian Alexander