Blocking the Imagination: Yoshida at the Dulwich Picture Gallery

Yoshida: Three Generations of Japanese Printmaking

In the porch of the Dulwich Picture Gallery in South London hangs a torrent of wisteria, festooning a poster for the current exhibition, Yoshida: Three Generations of Japanese Printmaking—a deliciously seasonal if subtle echo of the show inside.

In the first room of the exhibition, devoted to Yoshida Hiroshi, the paterfamilias of this extraordinary dynasty of woodblock artists, is a captivating image of more swathes of wisteria. It’s perfect in every detail, which is the mark of the finest woodblocks in the Japanese tradition. The blossoms are reflected precisely in the lake below with delicate shade changes.

But it’s not true—the garden is wholly imaginary, an example of the design concept Hiroshi introduced called shakkei, or “borrowed landscape,” in which a scene is enhanced by added notional charms, or even completely fake. Coincidentally, the wisteria in John Soane’s handsome portal is fake too.

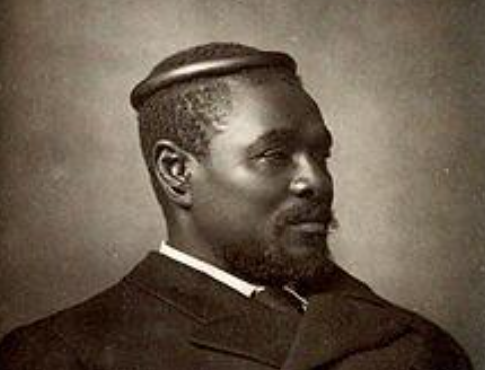

Hiroshi started his career in the tradition of Japanese woodblock set by Katsushika Hokusai, who died 26 years before Hiroshi’s birth. Both were taught in the Ukiyo-e tradition of painting, which was devoted mostly to portraying famous geishas and Kabuki actors.

Hokusai moved on, applying his woodblock techniques to nature and gradually eschewing traditional practice. The universally popular exemplar is his Great Wave off Kanagawa, the most reproduced image in the world. He transformed what had been a staid practice into a radical new genre, though still recognisably Japanese.

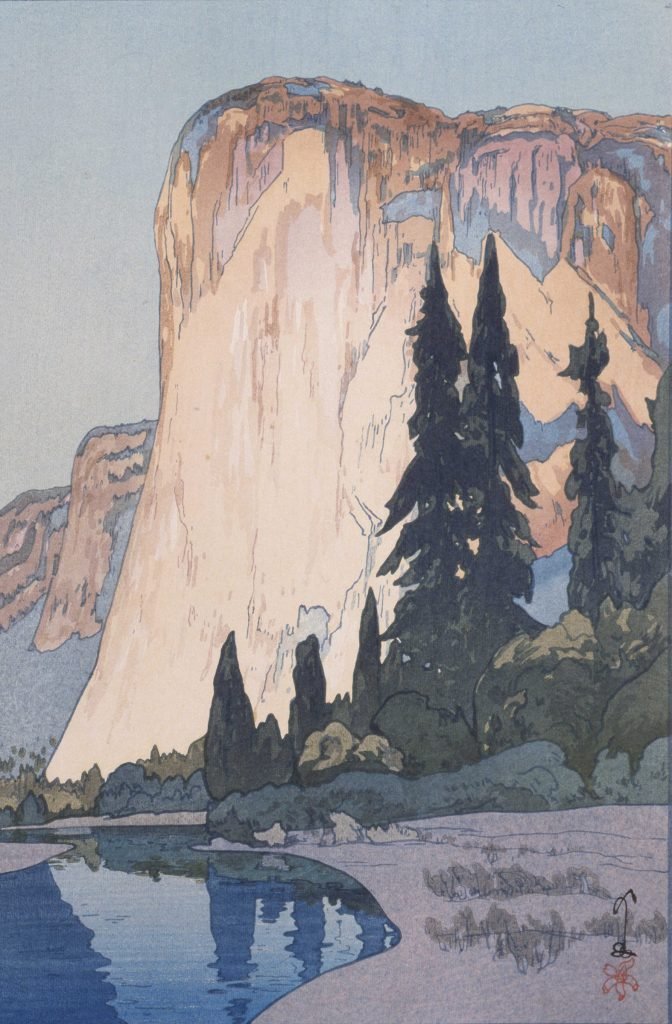

Like Hokusai, Yoshida Hiroshi—who abandoned his birth name of Ueno to adopt that of his art teacher, Yoshida Kasaburo—changed his way of working completely halfway through life. He had been a Western-style yoga painter until he was 44, when he joined the new print movement working in woodblock, adapting ukiyo-e and becoming a pioneer of the shin hanga movement, incorporating Western tropes in what became his famous landscapes. Unlike Hokusai, Hiroshi travelled widely abroad to the United States, Southeast Asia, and Europe—he even visited the Dulwich Picture Gallery in 1900 aged 25.

This exhibition tells the story of a small family of six individuals whose choice of genre, a particularly exacting one, they mastered, manipulated, and made, eventually, into portfolios that came to owe little to recognisable national characteristics in a growingly global art market.

Yoshida Hiroshi was born in Kyushu in 1876, and his talent as a painter was spotted early on by his secondary school art teacher, Yoshida Kasaburo, who adopted him at the age of 15. Hiroshi studied with Western-style painters, yoga-ka, and at 17 continued his studies at Tokyo’s Fudosha painting school. His reputation grew at home and abroad, with his first American exhibition in Detroit in 1899, after which he went travelling, exhibiting in the Paris Exposition of 1900 and in the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Yet, the family that was to come were blissfully unaware of his fame abroad—his granddaughter Ayomi, born in 1959, was 31 before she saw the cherry trees print in Detroit and for the first time realised that Hiroshi had worldwide renown.

However, it was not until about 1920 that Yoshida produced his first woodcut, a depiction of a shrine. In 1923, he was back in the States where he found a growing enthusiasm for Japanese prints, and his woodblocks started to show a combination of ukiyo-e and yoga, like the magical imagery of his Kumoi Cherry Trees seen here. In 1925, he started his own studio and began his series of European and American prints, the Alps and Venice’s canals, for instance. He died in Tokyo in 1950, aged 73, after returning from another painting excursion around Japan for the last time.

His work was painstaking—there is a display of the tools Hiroshi used, with a short film about his studio. He would normally use as many as ten overlaid colours to give increasing depth to a print and take anything from 30 to 100 impressions. Somehow, he was able to portray the dry air of the Egyptian desert and the damp atmosphere of urban Japan.

Hiroshi’s wife, Fujio, who died in 1987 aged 100, was also a renowned watercolourist and printmaker, the first woman in Japan to study Western-style painting, and the first Japanese female artist to gain a reputation abroad with her close-ups of flowers and floral motifs that verge on the abstract, like this Yellow Iris (see top)—she would put the flowers in fishbowls to magnify their details.

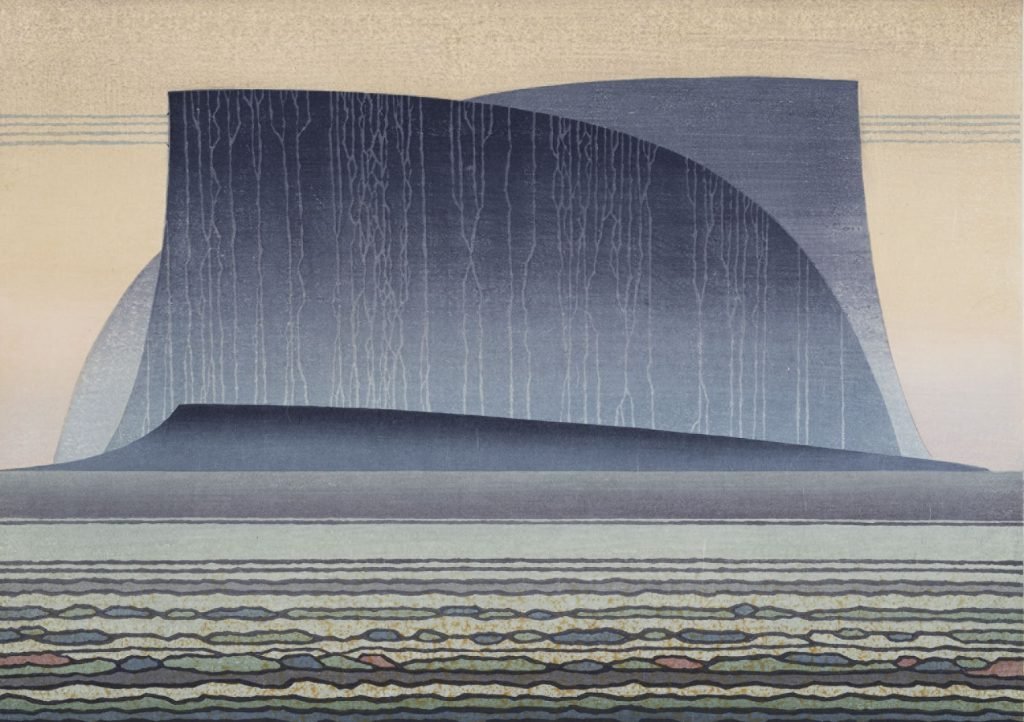

Their eldest son, Toshi, born in 1911, started in his father’s shin hanga footsteps but then developed his own style, trying new ways of applying colour to add more drama to his woodblocks. You can see him here starting with startlingly delineated townscapes, but in the 1940s graduating to abstract prints that found a new facet to the genre. His close-up of canal waters in Bruges is a mesmeric evocation.

His brother, younger by 15 years, was Yoshida Hodaka, who broke away from family practice by incorporating collage and photo-etching into his work, inspired by Pop Art and Surrealism. His Profile of an Ancient Warrior betrays his admiration of the Spanish painter Joan Miró. His wife, Chizuko, was also a feted artist who co-founded the first group of female printmakers in Japan, and her work absorbs the influence of Abstract Expressionism.

Their daughter, Ayomi, is the last of the Yoshidas. Her technique, still following the woodblock tradition, has harnessed new technology to create immersive works enveloping whole rooms and those within. The last room in the exhibition is hers, containing a single piece. Called Transient Beauty, it’s inspired by her grandfather’s early masterpiece, Kumoi Cherry Tree, commissioned for and built in the gallery that her grandfather first visited over a century ago. It is a dream-like experience in the Japanese tradition, but unlike Hiroshi’s visions, this one is ephemeral: when the exhibition ends, it will disappear forever.

Dulwich Picture Gallery, until November 3