Medieval Women at the British Library: Shaping Art, Culture, and Society

I’m usually asked to write about art for these pages, but Medieval Women: In Their Own Words is not an art exhibition. It is, though, a story about culture, our whole culture, because until relatively recently European and Western history describes only half of our past.

Nor is the show ostensibly about creativity, about women’s alleged special gifts with needle and thread, for instance, but creativity seeps into every aspect of the story of that part of society that in medieval times had no rights against husband or father.

The general assumption has been that art – literature, music-making, painting (particularly in the illumination of manuscripts and books) – was done by men, that rulers were male, that doctors were male, that farmers and craftsmen were always male. Men did the talking in history, and men wrote the history.

This British Library exhibition retells that story through the female written word. There are elements of exceptional women in history that we know. We know about Christine de Pizan, the first professional female author; of the polymathic nun Hildegarde of Bingen, whose musical compositions still thrill concert audiences; and of Margery Kempe, who wrote the first no-holds-barred autobiography in English. But were they the exceptions? The curators of this exhibition have unearthed from the Middle Ages many more female personalities to give us a rounded image of medieval women, in private, in public, and in religion – so much more important in every aspect of the Middle Ages than it is today.

Explore More Arts & Culture Features

Monet’s Journey Through London’s Fog

There is a curious modern parallel in the restoration of the 12th–13th century Notre-Dame, Paris’s magisterial cathedral that was badly damaged by fire in 2019 and reopened in November. No women were credited with having a hand in its building, but 51% of the workforce that has restored it in the 21st century have been women.

“God has given women such beautiful minds to apply themselves, if they want to, in any of the glorious fields where glorious and excellent men are active,” wrote de Pizan (1364–c.1430), in her tour-de-force The Book of the City of Ladies. She was an Italian-born French court writer, who also wrote biography, poetry, and love ballads. City of Ladies was written in French vernacular prose, and she was a robust defender of female qualities and virtues against the prevailing misogynistic fashion in writing. But she only embarked on what became a renowned career after the death of her husband and her father within a year of each other, which forced her to confront penury or somehow earn her own income to support her three children.

An exquisite illustration from her books in this exhibition shows her City of Ladies, in which crowned dames are seen not only reading but apparently decorating ceramics, wielding what seems to be a ruler and even building a wall with bricks and mortar. Who would have painted this page – a man?

Much of these fantastical illuminations are from the British Library’s own matchless collection, and the curators are able to show not only the role of women and their importance, but how revered some of the personalities were. A 15th-century illustration shows Margaret of York, the sister of Richard III and Edward IV (and herself the Duchess of Burgundy), not only in devotional prayer but apparently in direct conversation with Christ. You can’t get nearer the top of the tree than that.

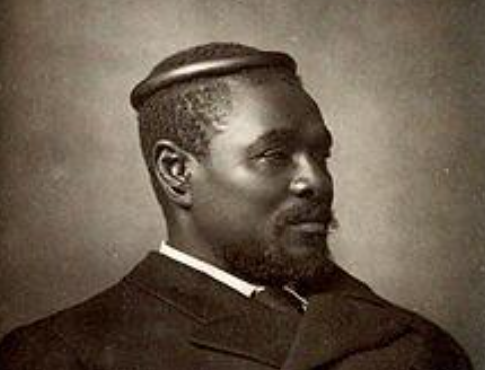

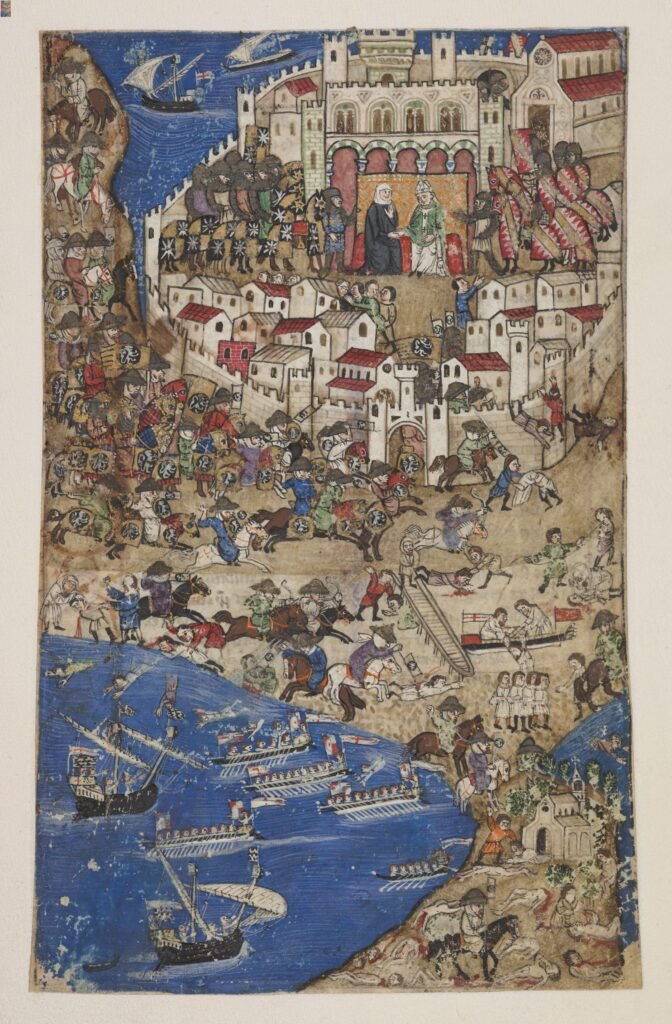

Women, like the 13th-century Lucia, Countess of Tripoli, could wield their own power. Out of the chaos in the city-state following the death of her brother, the count, Lucia seized control herself, made treaties and political liaisons, and in 1289 she faced a siege by Italian forces. Despite eventual defeat, Lucia emerged as the hero, and in an extraordinarily detailed exposition of the battle the countess sits calmly in her castle in the heart of the painting, hand-in-hand with a bishop to show her Christian credentials in a Muslim part of the world. From the 1420s is a testament to another extraordinary woman operating in a medieval man’s world: Joan of Arc, who may not have been entirely literate but was able to sign a demand for ammunition, and here is her signature on a document being seen outside France for the first time.

Women also made a huge contribution to music-making, and they took it very seriously, as a page from a 14th-century Gradual, or music manual, shows: the Poor Clares of Cologne ran a workshop producing decorated manuscripts, sometimes on commission from outside their convent, and the page in the exhibition is from a choir book.

But the everyday preoccupied medieval ladies as much as the spiritual, and we have a large volume devoted to the creation of cosmetics, and some of the aromas have been recreated for the display based on these recipes. And while the assumption is that all doctors were male, it’s a wrong one. Not only were there women apothecaries, but there were also female clinicians, because women were often unwilling to take gynaecological problems to a man who may not have had the understanding of feminine physiology, or sympathy, that another woman would have.

And, although recent scholarship is suggesting that the teams (over perhaps 17 years) that created the Bayeux Tapestry may well have included male embroiderers, women’s needlework was pre-eminent. To make the point, an altar band from the early 1300s is sewn with intense devotion but with great joy in the colours and flourish in the stitching – and this one, we know, was made by a nun from Beverley called Lady Joan because this is the only one to survive with a signature.

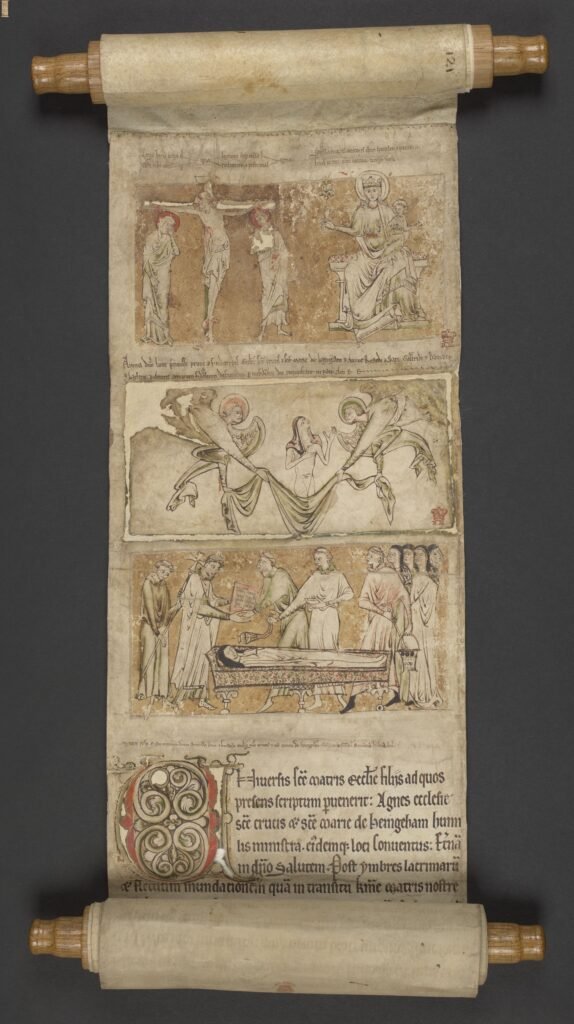

If medieval nuns spent most of their lives in enclosed communities, they could also have a national profile. Towards the end of the exhibition we meet Lucy, the first prioress of Castle Hedingham Priory in Essex. When she died in 1225, the Benedictine nuns created a roll in her honour, beginning with illustrations from her life and ascent into heaven, but followed by messages in her memory from over 120 religious houses, most if not all of them convents, nunneries, and nuns’ abbeys, written in sublime script, and it was on the road for five years. However secluded, however fraught travel was in the early 13th century, they all knew Lucy.

Through these 140 items, this exhibition is the first to acknowledge the diverse contributions the female half of the population made to medieval life. More will undoubtedly come, with new discoveries emerging from libraries, archives, and archaeological excavations. Through these literary and creative finds, medieval women declare themselves, that they had personality, presence, and things to say. Christine de Pizan would surely have approved, but undoubtedly would have added, “What took you so long?”

Learn more about the Medieval Women: In Their Own Words exhibition on the British Library’s official website.

For more insights into how women shaped art, culture, and society throughout history, visit EyeOnLondon for the latest reviews, features, and updates. Keep exploring with us!

Exhibition Details

Exhibition: Medieval Women: In Their Own Words

Location: British Library, London

Dates: 1st February 2025 – 31st May 2025

Opening Hours: Monday – Saturday: 10am – 6pm, Sunday: 11am – 5pm

Tickets: Adults £16 | Concessions £12 | Under 18s £8

Website: British Library Official Website

★★★★★ Rated 5/5

Follow us on:

Subscribe to our YouTube channel for the latest videos and updates!

We value your thoughts! Share your feedback and help us make EyeOnLondon even better!