Steinway in London: Inside the Workshop Powering the Proms

With the Proms in full swing, the London showrooms, studios and technicians of Steinway Pianos will be furiously busy. Instruments will be made ready for the Royal Albert Hall on an almost daily basis, the pianists themselves will be booking times to practise on either the instrument they will use for their Prom or one with similar specifications, others will be dropping by to talk to the chief technician about the sound they want. Pianos will be despatched to major festivals where the venue does not have its own instrument or a soloist has asked for a favoured one to be brought in. Then, of course, there will be people coming in to buy one or arrange for their family’s cherished Steinway to be reconditioned.

The pianos of Steinway & Sons now dominate the world’s concert halls and are particularly associated with the big romantic concertos and most virtuosic soloists. One might think that they were one of the great companies that emerged to service the orchestras of Vienna, Berlin and Amsterdam at the turn of the 19th century. That would be to place the firm in the wrong place and time. Heinrich Steinweg, a carpenter who had served in the Napoleonic wars and turned his hands to making guitars and zithers, built his first piano in the kitchen of his home in Seesen, south of Hanover, in 1836. The idea paid off but in 1850 he emigrated with his family to New York and anglicised the name to Henry E. Steinway. One son was left at home to continue the original firm.

At that time piano building was all the rage in America. There were hundreds of builders and every middle-class home, bar and hall had one. Henry and five of his sons went to work for different companies to spot the trends before starting their own company under the familiar name in 1853. Their success was extraordinary and a dozen years later they had built a 2,000-seat concert hall on 14th Street that also became the home of the New York Philharmonic. The greatest pianists of the day, like Liszt and Anton Rubinstein, were extolling the qualities of the instruments, a tradition of endorsements that the company has taken pains to foster ever since.

Craig Terry, Steinway’s Managing Director in London, who has been with the company for 40 years and in London since 2011, told me, “At the beginning the US domestic pianos were different. They made hammers with a softer, more rounded sound than European pianos, liked by women players with smaller hands.” When the company began focusing on concert pianos, the character changed. “The American piano became beefier and had more power: much better for concertos and the new big concert halls.”

The first London shop opened at Seymour Street, the western extension of Wigmore Street, in 1875. The bound ledgers of who bought the pianos, and which model, go back to the start; for example, a Mr Alcock bought a Style 2 Grand in 1876. Four years later the company reopened its German workshop, this time in Hamburg, and the factory has been in that city ever since. Now, 145 years later, Craig says, “The NYC factory is in Queens. It only supplies the Americas. Hamburg supplies Europe and Asia but since so many Europeans travel to the US they will have a Hamburg piano waiting for them there too.”

The family sold the company to CBS in 1972 and it went through several corporate owners until it was brought back into private ownership in 2013 by the billionaire hedge-fund manager and prominent Donald Trump supporter, John Paulson, who was a major beneficiary of the 2008 banking crisis that crippled the world economy. Whether that has any effect on pianists’ attitude to the company is not yet clear. It is quite likely that many are not aware of the fact.

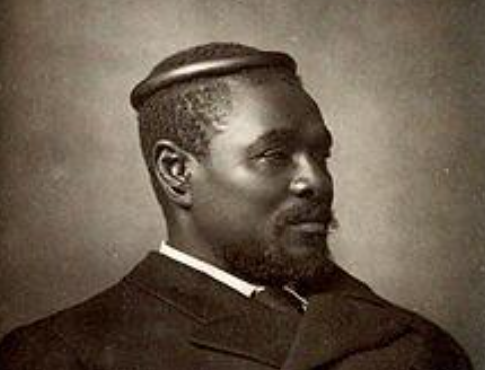

Pianos are not responsible for politics, of course – though one of the early champions of Steinway was Ignacy Paderewski who was, for a few months, the first Prime Minister of independent Poland in 1919. His is one of the photographs displayed with pride in the hall of Steinway’s modern showrooms in Marylebone Lane, into which the company moved in 1982. The hall seats 40 and is available to signed-up Steinway players to practise in or prepare for concerts. Only Steinway artists can use the main studio. On its walls is a ‘rogues’ gallery’ of pianists past and present, from Paderewski to Clare Hammond. The tiers of pictures show the regiment of great players associated with the company to impress prospective clients but also give confidence to present performers that they are in a secure and exalted tradition. On most Wednesdays there is a public concert in the small hall, often giving a chance to young pianists who are just finding their way into the profession.

In the shop there are always three of each model on show, from the uprights, starting at £56,000, through the smaller grands between five and a little over seven foot in length for between £95,450 and £200,400, to the concert grand, the famous Model D, at a fraction under nine foot and costing £200,000. Like Rolls-Royce, clients can have bespoke colours and accessories that push the prices up even further. If all that is a little too daunting, Steinway have pianos with the Boston label for a third of the price: good for families and schools, made under licence in Japan. The offer is that if you buy one now you can trade it in for a ‘real’ Steinway in 10 years and get the initial price knocked off as a discount.

Down in the basement are the workshops where pianos are taken apart and lovingly refurbished – not just the concert grands. There are much-loved family uprights getting the same care and attention and there is a pervading smell of new wood and varnish. The same technical team that work on the concert pianos recondition the retired ones. The technicians are also preparing each concert piano to suit the hall and the performer. The day I visited they were working on a piano going to Windsor Castle in the morning for a BBC Young Musician of the Year to play for King Charles. It would be back in the workshop the next day after the event, transported in a specialist van with climate controls.

For many of London’s halls the pianos live in Marylebone Lane and are rented out when needed, although the Wigmore Hall around the corner has three of its own. Steinway’s chief technician and Director of Concert and Artists’ Services, Ulrich Gerhartz, says, “A piano for the concert hall is like an F1 car and we treat it in the same way [without the crashes]. A concert hall grand has eight to ten years of life because of wear and tear on the tuning pins. Then we retire it and sell it on second-hand to a church or small hall. Each professional player will have the instrument prepared to their own specifications, for example whether they ask for forward projection or a softer sound.” He refutes the often-stated claim that the company’s pianos have an over-bright hard sound. “It’s not true. If one is, it is because the pianist or hall has asked for that sound and the technician has manipulated it by hardening the hammers.” Given normal use outside a concert hall the pianos can be expected to last 60 to 70 years without rebuilding. “The twin enemies,” Ulrich says, “are dryness and humidity. In Hawaii, for example, the salt and humidity mean the strings just rust.”

Discover more stories that bring London’s music, culture and history to life. Follow EyeOnLondon and stay connected with the people, places, and performances that shape the city.

[Image Credit | Steinway & Sons]

Follow us on:

Subscribe to our YouTube channel for the latest videos and updates!

We value your thoughts! Share your feedback and help us make EyeOnLondon even better!