Autumn Listening: Simon Mundy on the Month’s Best New Classical CDs

Autumn’s classical CD reviews often arrive in a welcome flurry, many timed for the start of the concert season. In this month’s round-up, Simon Mundy reviews music ranging from Haydn’s early symphonies to Poulenc’s wry neoclassicism, Schumann’s restless Romanticism and the devotional intensity of Gesualdo and Bruckner. What links these discs is a sense of musicians thinking carefully about their composers, not merely playing the notes. They are recordings to sit with, listen to whole, and return to as the evenings draw in.

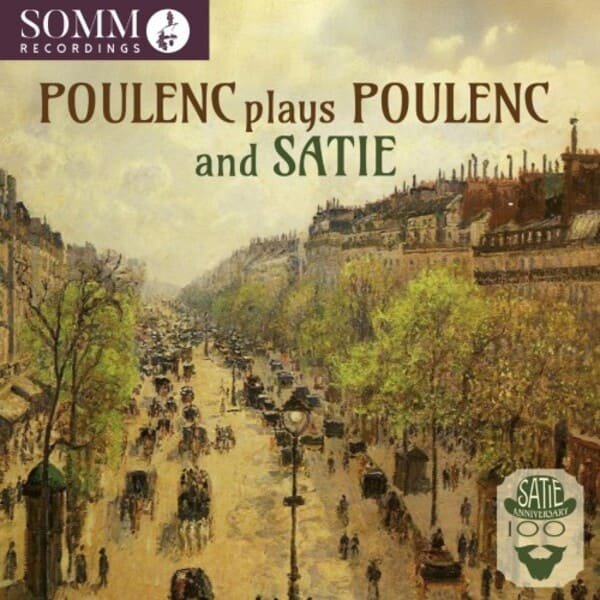

Poulenc plays Poulenc and Satie

Francis Poulenc (piano); Jacques Février* (piano); Orchestre National de la RTF* / George Prêtre (conductor); Orchestre des Concerts Straram** / Walther Straram (conductor) — SOMM Recordings ARIADNE 5041

Poulenc

Concerto for Two Pianos*

Aubade – Concerto for Piano and 16 instruments**

3 Mouvements perpétuels, Nocturne in C, Suite Française

Satie

Descriptions automatiques, Gymnopédie No. 1,

Gnossienne No. 3, Sarabande No. 2,

Avant-dernières pensées,

Croquis et agaceries d’un gros bonhomme en bois

The one thing guaranteed about listening to a composer playing his own music is that we know it is how it is meant to go. We can have no quibbles about tempi and phrasing, and Francis Poulenc was a fine, if not virtuosic, pianist. Sensibly, he wrote parts that he could play well. He made these recordings between 1930 and 1960, with the solo piano pieces by him and Erik Satie played in CBS’s studios in New York in 1950. They reveal his sensitivity and care for the musical line above everything else. The Concerto for Two Pianos, one of his most neoclassical works, was recorded for a 1960 film, and the Aubade right back in January 1930 for Columbia Records. Recording technology changed massively over those thirty years, and the audio restoration by Lani Spahr is impressive, especially for the earlier recordings. The piano itself always comes out best in such restorations, and it is the other instruments that sound a little cramped by modern standards. The point is, though, that this is a superb composer talking to us directly. A must-have for any lover of his music.

Arts & Culture — Latest from EyeOnLondon

Discover recent features and reviews from across London’s cultural scene.

Queen Camilla’s Royal Family Order

What the new award means for royal portraiture, precedent and protocol.

Read the storyMore Arts & Culture

Hogarth’s ‘The Pool at Bethesda’ restored

An 18th-century canvas returns to public view after careful conservation.

Read the storyMore Arts & Culture

June Classical Music Reviews

Simon Mundy’s highlights from new recordings across the repertoire.

Read the storyMore Arts & Culture

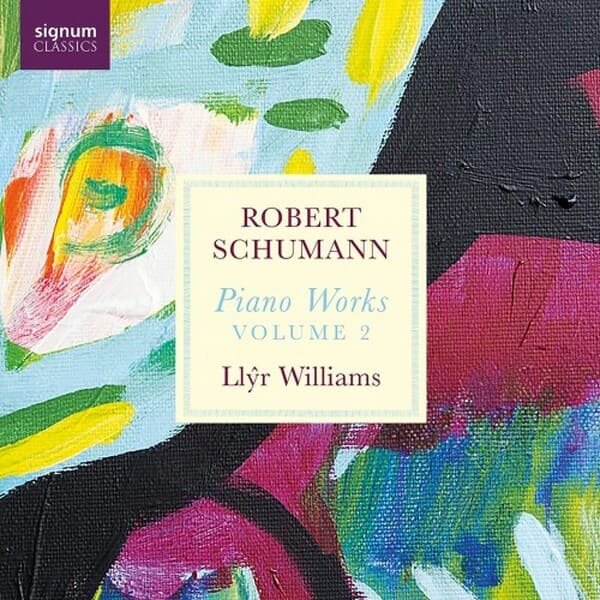

Robert Schumann: Piano Works Vol. 2

Llŷr Williams – Piano · Signum Classics (2 CDs) SIGCD923

Programme

Piano Sonatas Nos. 1 & 3 · Kreisleriana

Études symphoniques · Arabesque Op. 18

Blumenstück Op. 19

Llŷr Williams is every inch the virtuoso pianist but is also good at musical architecture, as he has to be in the Schumann Piano Sonatas, which, though early works, are not the easiest to keep in shape, being full of the composer’s excitement with the Romantic movement. All the works here were written in the 1830s, when Schumann was in his twenties and besotted with first Ernestine von Fricken and then Clara Wieck, though not yet married to her. All of Schumann’s life was emotionally turbulent, but these were the years when he poured his tangled feelings into his piano music.

Williams catches the constant lovesickness of Kreisleriana expertly while still managing a remnant of social decorum. The Études symphoniques were not organised as a complete set until Clara and Brahms set about the task many years after Robert’s death. Despite this chaotic history, Williams has come up with his own sequence for the pieces, so that they hang together as an effective set of variations. They draw on the études tradition established by Hélène de Montgeroult, whose collections both Robert and Clara had studied. Williams makes a strong case for following his suggestions, and the études become the most satisfying pieces for home listening on these discs.

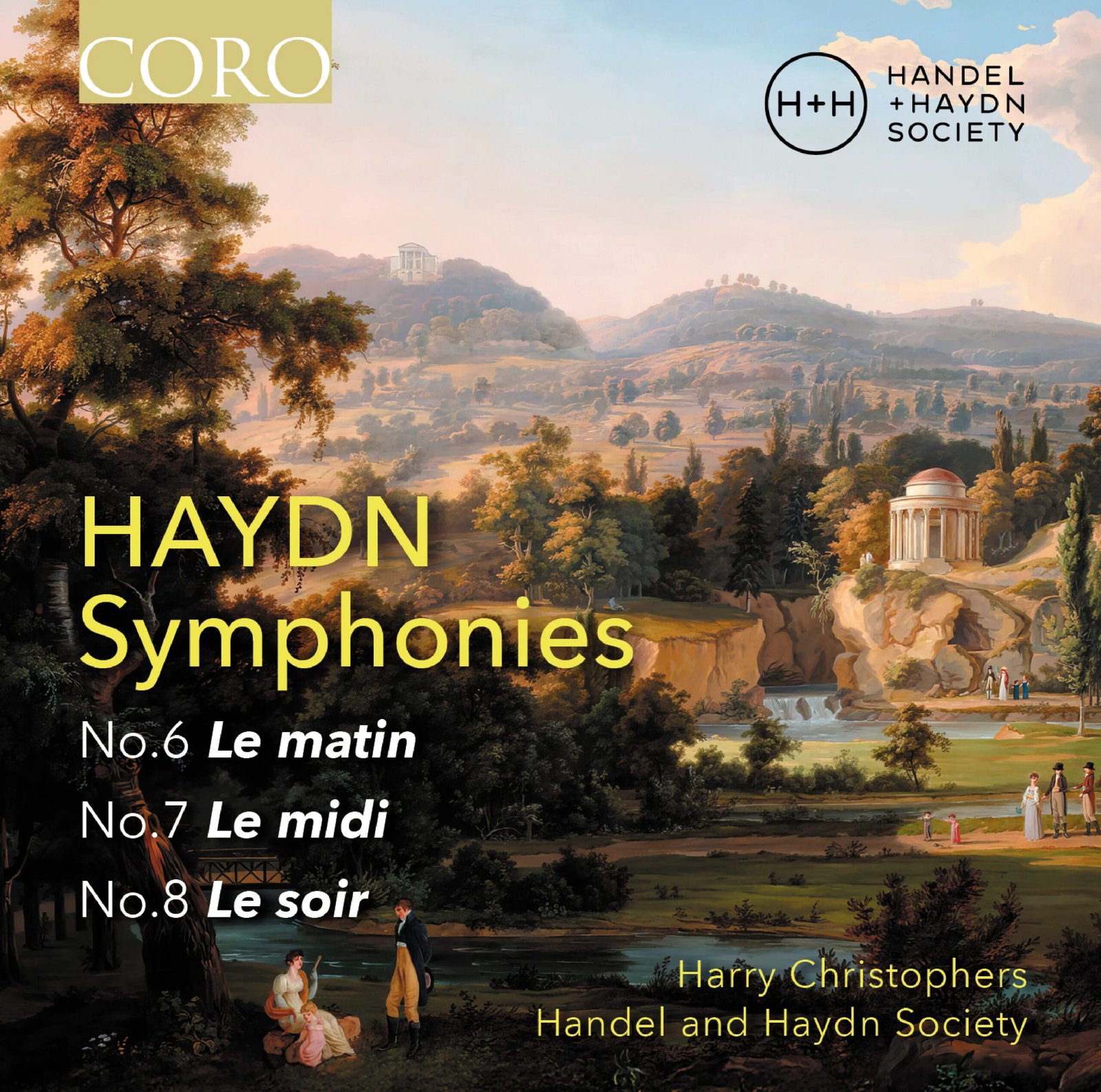

Haydn: Symphonies Nos. 6, 7 & 8 — Le Matin, Le Midi, Le Soir

Handel and Haydn Society, Boston — Harry Christophers, Conductor · CORO 16214

Programme

Symphony No. 6 in D major Le Matin

Symphony No. 7 in C major Le Midi

Symphony No. 8 in G major Le Soir

It is salutary for Europe’s orchestras to realise that Boston’s Handel and Haydn Society Orchestra was founded in 1815, only six years after Haydn’s death, and has thrived ever since, unlike many of its counterparts on this side of the Atlantic. It is the USA’s oldest arts organisation and is now directed, as Conductor Laureate, by Harry Christophers, that doyen of British period-performance conductors through his other ensemble, The Sixteen. It is hardly surprising, then, that this recording of three titled symphonies reeks of suave assurance.

These were among the first works Haydn wrote for the Esterházy Palace in Eisenstadt, and they must have made some summer evenings delightful. By giving members of the orchestra so many solos, they are quite close to the concerto grosso form, by 1761 only just going out of fashion in favour of the new term, symphony.

There are plenty of good recordings of these works, but I cannot think of any that are notably better. This is one of those records that it is always tempting to pick when relaxation, not intellectual complexity, is the order of the evening.

Bruckner & Gesualdo: Motets

Monteverdi Choir – Jonathan Sells, Director · Monteverdi Productions SDG736

Programme

Motets by Carlo Gesualdo and Anton Bruckner

Palestrina (arr. Wagner): Stabat Mater

Lotti: Crucifixus a 8

Music could hardly be less relaxing than these works. They are infused with devotional tension. Gesualdo and Bruckner may have been separated by 300 years, but in both cases their music is wracked with passion: in Gesualdo’s case agonised, in Bruckner’s born out of sheer conviction. The latter’s motet, Christus factus est, is magnificent to sing. Bruckner was never afraid to invest his faith in fine melody.

Palestrina’s Stabat Mater (from the generation before Gesualdo) and Antonio Lotti’s Baroque Crucifixus fit well into this company, linking the two main composers to the continuity of the a cappella tradition. The Monteverdi Choir was Sir John Eliot Gardiner’s own ensemble for so long that it is strange to hear it under different direction. Jonathan Sells, though, is as much a singer as a conductor, and this repertoire comes naturally to him.

The pacing is unhurried but never too slow, the crescendi and diminuendi handled with sure instinct. Best of all is the choir’s diction, always clear without sounding too pedantic. This is a cleverly devised and beautifully sung album.

For reviews, interviews, and features from London’s arts scene, follow EyeOnLondon for intelligent coverage that keeps you in the know.

Follow us on:

Subscribe to our YouTube channel for the latest videos and updates!

We value your thoughts! Share your feedback and help us make EyeOnLondon even better!