BBC Proms 2022 Royal Albert Hall 2 & 3 August

by Simon Mundy

On consecutive nights the Prommers saw two relatively young conductors who might seem to have little in common, the very English Nicholas Collon and the very Californian Ryan Bancroft. They have both recently been appointed to direct Scandinavian orchestras of great prestige: Collon the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra (the first ever non-Finn to do so) and Bancroft the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic. The secret that makes them so attractive to players and audiences is that both believe in giving their musicians the freedom to express themselves within the ensemble. They are never dictatorial ‘maestros’, that ghastly term so beloved of the conductors of the 20th century, and which is gradually falling from use in this, thank heavens.

They demonstrated the result brilliantly with their British ensembles in two iconic symphonies written a century apart, Collon in Beethoven’s Fifth and Bancroft in Mahler’s Fourth. The Aurora Orchestra have become known for their fascinating performances with the orchestra playing entirely from memory, in the way an opera singer or many soloists do. When they take on that challenge, they also stand (with the obvious except of the cellos), a practice that is common in baroque ensembles, but is very rare for those specialising in music after 1750. The result is a huge increase in expressive energy, both from the musicians themselves who have the freedom to move as a soloist does, but also from the audience, who have a degree of visual stimulation that helps them concentrate instead of letting the music flow passed.

violin) perform Iannis Xenakis: O-Mega, Dmitry Shostakovich: Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor and Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony from Memory in the Royal Albert Hall on Tuesday 1 August 2022.

Photo by Mark Allan

In this prom, the performance was preceded by the Presenter Tom Service and Collon analysing the themes and structure of the Fifth Symphony, not only with articulate fluency but with the help of the note-perfect orchestra moving around the stage, completely altering the relationship between the sections – sometimes with the winds at the front, or violins split at the back, which made so much of Beethoven’s thinking clear; as Anthony Hopkins used to explain to audiences, with the help of the orchestra, fifty years ago, but this was on a whole new level of clarity.

Before the symphony the Aurora players were sitting and had the music for Shostakovich’s First Violin Concerto and here it was the soloist, Patricia Kopatchinskaja, who provided the movement. She is a small bare-footed tornado on stage, attacking Shostakovich’s rhythms with fury and then dwelling on the agony of the quiet passages, completely embodying the composer’s denunciation of autocracy and state brutalism. It was preceded by the tiny final work by Xenakis, written a couple of decades ago for the London Sinfonietta. He called it Omega and with just four strings, four wind, four brass and a drum, it is the full stop to his composing, and like the Shostakovich and the Beethoven deeply defiant.

The next evening was more conventional but just as rewarding. Caroline Shaw is 40 this year and it began with her Entr’acte, a supremely clever piece for strings, causing the listener think that its structure and harmonies are familiar and predictable, but then crumbles before gathering back into a sumptuous chord, then crumbles again. It finishes with the most delicate of cello solos, played with riveting intensity by Alice Neary. In Bancroft’s time as the Cardiff-based BBC NOW’s Principal Conductor, he has developed its string section into one of the best in Britain and by following the same path as Collon; giving the players the freedom to express themselves and take responsibility within the confines of the ensemble, much as Mark Elder has done with the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester.

When we came to Mahler’s Fourth Symphony, the sense of movement that had prevailed the night before returned: not in physical form (though Ryan Bancroft started out as a dancer) but in the interpretation. Bancroft says that in Mahler, even when he is being grotesque and angry, everything must fit within the natural momentum of the underpinning dance. He made sure of that, carrying the music along with the lilting passion that makes this the most joyous of Mahler’s music. The hymn to rural life in heaven (slightly grizzly if truth be told) from Das Knaben Wunderhorn, which comprises the last movement, needs a singer who can sound opulent and innocent at the same time. Miah Persson was the perfect fit.

Less perfect, sadly, was the behaviour of the audience, who coughed, cleared their throats, dropped their programmes and crunched their plastic drinks holders on both evenings as if they were at home watching telly. The prize for the crassest person that evening, goes to the woman who coughed as loud as timpani in the exquisite transition between the last two movements of the Mahler.

Images: Mark Allan

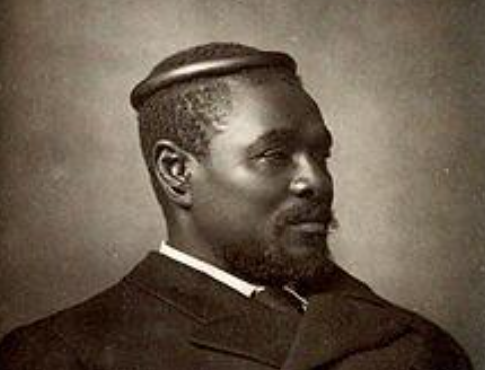

Patricia Kopatchinskaja Violin

Aurora Orchestra

Nicholas Collon Conductor

Miah Persson Soprano

BBC National Orchestra of Wales

Ryan Bancroft Conductor