An Artist’s Actor

by Sophie Pretorius

I think I saw a very different show at the Tate Britain than that of other London journalists. However, we all agree it was excellent. Walter Sickert, which opened at the Tate on 28 April and runs until 18 September 2022, shows off the range, humour and modernism of this thoroughly under-rated British artist.

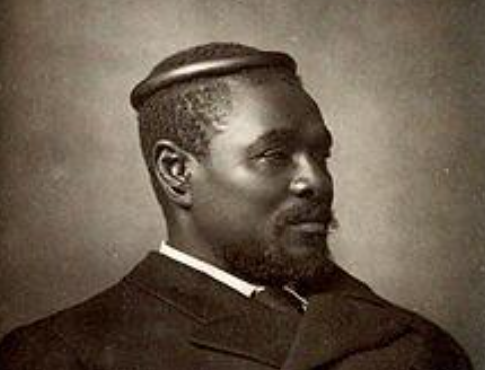

An actor who changed careers suddenly, but who retained a penchant for dressing up, a philanderer with a high sense of romance, a radical but simultaneously deeply traditional painter; Walter Sickert was many things, but he was not a murderer. If you have read any of the reviews of this show, you might be surprised to learn that his status as a suspect for the murders of Jack the Ripper, is not mentioned once in the exhibition. Unlike last year’s small show of his work at Piano Nobile Gallery, where it seemed that this was all the press, and visitor alike, could talk about.

I feel very sorry for Sickert scholars and fans that this speculation takes up most of every discussion of his work at present. So, I will state quickly and simply, Sickert was fascinated by the murders, as was all of London at the time, and perhaps took more of an interest than most, but the evidence produced 100 years, after the tragic murders linking him to the murder of those 13 women, is flimsy. The book which raised these suspicions, Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper—Case Closed by crime novelist Patricia Cornwell (2002), is a Dan Brown-esque romp, which hinges a case on some very shady evidence that has since been disproven. However, the allure of the story is difficult to quash.

The show is marvellous, and though portions of it, of course, bear the foreboding deconstructive air that later artists so admired him for, what Sickert comes out of this exhibition looking like, is a talented impressionist, and a very French one at that. The walls in the first couple of rooms of the exhibition are painted in the most wonderful yellow ochre, which makes the patrons of the gallery look astoundingly beautiful. It temporarily made me feel optimistic about the beauty of my fellow man. In these rooms the early paintings stand in stark contrast to the sunny walls. They are dark, so dark that it is sometimes difficult to tell what they depict. They are usually of shop exteriors, and in them, one can see a young Sickert playing with his oil technique, turning slowly towards a more considered approach, and away from his alla prima, wet on wet, style.

The third and fourth rooms focus on the music hall scenes, which Sickert used as a sort of academy of human emotion, utilising mirrors and miscaught stares in a manner that brings to mind Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882.

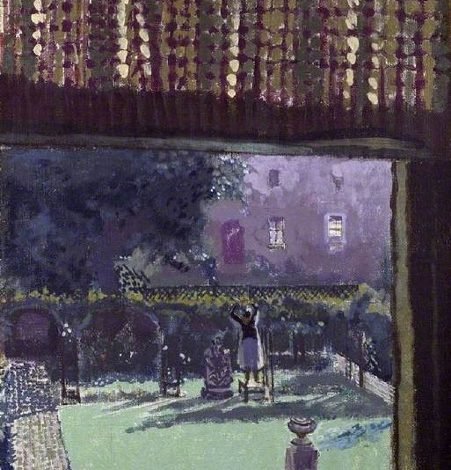

On the subject of French-ness, the most surprising rooms to me, come after these and before the nude room. Their subject matter is largely French; being bright, cheerful, and accomplished. They are accomplished in remarkable shades of jewel pastel; just beyond avocado green and plum, with some white. In Lainey’s Garden (The Garden of Love), c.1927–1931, one can see that they depict a period of apparent marital bliss and all present a mysterious radiance absent from Sickert’s earlier and his later work.

Then comes in the nude room. For all the talk of murder, and all the comparisons of these paintings to the gore of Francis Bacon, there is absolutely no blood. The paintings mostly have punning titles, or perhaps the paintings themselves pun, particularly around the word domestic. They are shocking, but more because of what they do not depict than what they do.

The last room reveals late Sickert to be the dyed-in-the-wool romantic and pioneering modernist that he was. A Daily Express news article from 1930 reproduced in a vitrine in this room, bares the title ‘A novel portrait of the King, Picture painted from a press photograph at the races’. It illustrates how extraordinary Sickert’s reliance on photographs, which anticipated the practices of Freud, Bacon, and many other great artists, was. Sickert has long been an artist’s artist, very well-known especially to the ‘school of London’ painters, but outside of this, hardly mentioned. I hope this show at the Tate will go some way toward rectifying this.

Walter Sickert

28th April – 21st September, 2022

Address: Milbank, London. SW1P 4RG

Tel: 020 7887 888