Victor Willing – Errant Knight

by Sophie Pretorius

It is very rare that you walk out of a Mayfair gallery excited and impressed by a selling show, and still more unusual that a male artist’s reputation needs to be rehabilitated because of the glare of his wife’s fame. An exhibition of Victor Willing’s work, which opened at Timothy Taylor (after the unexpected delay caused by Her Majesty’s passing) on 22 September is both impressive and rehabilitative. The display covers the late period of Willing’s practice, 1978-1986, during which time Willing, in the throes of his severe and eventually fatal multiple sclerosis, turned from his artistic identity as what John McEwen called the ‘big star’ of The Slade and the best student of William Coldstream, and began exploring the private symbols that he thought constituted ‘the real existence of [his] inner reality’.

The paintings are simple and bold, worked in densely pigmented short brushstrokes, as if straight from the tube, some are shockingly large. Paula Rego, Willing’s wife, remembers him taking up these ‘mile long’ canvases, and in a documentary made by their son Nick, she commented on the bravery and madness of the endeavour. The couple had returned to England in 1970 after Willing’s MS diagnosis in 1966. They had spent the previous 13 years in Portugal, during which time Willing had had something of an artistic crisis. Cassie Willing, the couple’s first child, stated that in this period her father’s ‘critical voice was catastrophic’. While Rego produced work at a dizzying rate in the adega on their property in Ericeira, in which they shared a studio, Willing had wilted.

Shortly after he left The Slade, in 1955, Willing had been given a show at the Hanover Gallery. He was popular and talented, and in with the right crowd. It was at this period, and largely through this gallery, that the careers of Francis Bacon, Henry Moore, and even those of the younger generation, like Richard Hamilton, were being launched, and all had seemed bright. The show at Timothy Taylor contains none of Willing’s nudes from this period, but they are marvellous and much-admired, especially those depicting Rego, with whom he was having an affair at the time.

Willing followed Rego to Portugal after getting her pregnant with Cassie, leaving his then wife, Hazel, and started to experiment with abstraction. This was not well received back in London, where his friends and supporters thought he should not abandon his nudes. Then followed his MS diagnosis. Multiple sclerosis is a chronic condition in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the brain and nerves. It can cause spasms, extreme fatigue, vision problems…the list is almost endless. Willing was only 38 when diagnosed and though the disease acted swiftly and painfully, it also seemed to lift the fog that Willing’s self-consciousness had created.

When they returned to London, Willing, now walking with the aid of a stick, and sometimes crutches or a wheelchair, began to paint images, which he described as appearing to him as visions on the wall of his Stepney Green studio. They came as a stream of deeply personal symbols, which he interpreted in a Jungian manner. They included scenes from his childhood in Egypt, simple elemental shapes and biomorphic forms, not unlike those of early Francis Bacon. He called what he was doing ‘hopeless painting with no ambition’, only conversing with himself, about images only he knew. This time his break from the style of his youth was well-received, he was given a show at the Whitechapel in the summer of 1986 by Nicholas Serota. Rego describes this show as having ‘made Vic’s life’. His family believes this show symbolised Willing’s being on the brink of an illustrious career, had he only been able to carry on. This is the narrative Timothy Taylor is pushing too, I find it a little steep. Willing was almost 60 at this point, and for someone who attended art college in their 20s, 60 is not the ‘brink’ of anything.

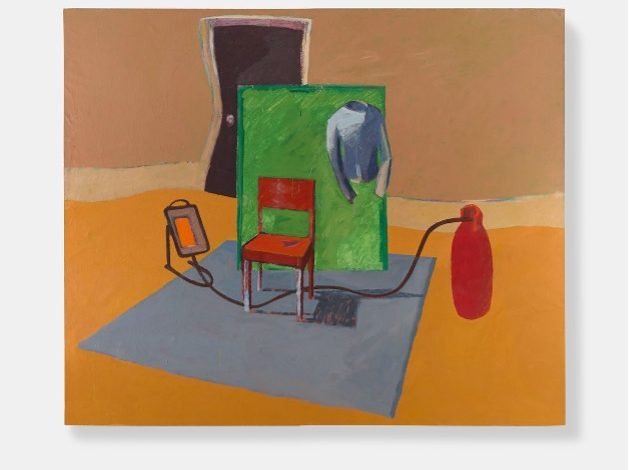

At the beginning of his son’s documentary, Willing’s methodical and thoughtful voice can be heard over a slideshow of his late paintings, ‘If my paintings get you then they get you before the sensible man has had any time to draw any conclusions about them at all.’ The works on the walls at Timothy Taylor are irrational images indeed, ideally for irrational consumption. The gallery gives no wall text and does not even provide the titles except for on a paper hand out. This works well, whatever it is that Willing is saying, you get it with no prompting, and then comes the inevitable process of rationalising this to yourself. They are affected in the way reading someone else’s diary is affecting. They share a fairy-tale aspect with Rego’s work, though perhaps Willing’s fairy-tale is more chivalric, and Rego’s more Grimm. They are populated by personal signs that convey an awful amount of feeling; a column, like a stick of butter, pops up again and again, an empty chair, empty clothing. One is struck mainly by the emptiness of even the densely painted works. They have that hot, stark emptiness that both the North of Africa and some of the South of Europe has to it, outside of the cities. John McEwan called them ‘reveries of space with a hint of menace’. Knight Errant, 1978 (reproduced), viewable on the first floor at Timothy Taylor, seems to depict the toilet of one of the nine malic moulds (or bachelors) from Duchamp’s Large Glass. Medical, lonely, and tragic, the empty chair sits warmed by a gas heater. The mythic task of the knight errant is to protect widows and orphans, and to wander the land performing noble exploits. There is a little canvas, also on the first floor, which is largely blank, it contains a noseless face painted in only four colours, it opens its mouth gormlessly in wonder and in pathetic incapability. Willing titled it Loser, 1986. He died two years later, at the age of 60. Like a mirror to his wife’s work, his practice was bound up in the promises and tragedies of masculinity.

Willing’s reputation has taken a long wander through the wilderness, during which time his prices have been scraping the floor. However, if Timothy Taylor’s optimistic (but not presumptuous) pricing of these works is anything to go by, perhaps enthusiasm and appreciation of his work can be restored to at least the place it was before his life and career were cruelly nipped, if not at the bud, then just before the fruit began to ripen.

Timothy Taylor, London

15 Bolton Street, W1J 8DG

22nd September – 5th November

020 7409 3344

Victor Willing, Knight Errant, 1978

© Victor Willing. Courtesy of Timothy Taylor, London/New York