From Plague Clouds to Preservation: Britain’s Early Warnings on Climate Crisis

As Britain’s industrial revolution swept across the landscape, it brought with it more than just technological progress—it laid the foundations for what we now understand as the climate crisis. From the late 18th century through the Victorian era, British artists, scientists, and intellectuals began to document the environmental transformations wrought by industrialisation. The ominous skies, smog-filled cities, and mechanised landscapes of that era were not just artistic subjects but early warnings of Britain’s early climate crisis warnings that were growing harder to ignore.

One of the earliest and most vocal critics of these changes was John Ruskin, an English art critic and social thinker who, in 1884, described the “plague cloud” looming over Britain. Ruskin’s stormy skies and descriptions of “polluted air” drew attention to the visible effects of coal-powered factories and widespread urbanisation, and his words continue to resonate in today’s climate discourse. His insights reveal an emerging awareness of industrial pollution that would later be understood as part of a much larger ecological threat.

The Early Warnings: Science and Art United

Long before the modern environmental movement, British artists and scientists collaborated in ways that allowed them to record and interpret atmospheric changes. John Constable, famous for his pastoral landscapes, turned his eye to the sky, documenting cloud formations that reflected the new atmospheric disturbances. His View on the Stour Near Dedham (1822), for example, seems like a peaceful rural scene, yet it hints at industrial influence on the landscape, as the river had been canalised to accommodate transport. This tension between natural beauty and industrial development underscored a growing concern about humanity’s intervention in the natural world.

Meanwhile, scientists like Thomas Forster were conducting studies on atmospheric phenomena, observing cloud patterns and weather changes influenced by pollution. His engravings of atmospheric studies captured early attempts to understand how industry was reshaping the air we breathe. These illustrations weren’t just scientific documentation; they served as visual warnings, hinting at a polluted future if the industrial path continued unbridled.

Nature’s Fragility: From Conservation to Exploitation

In Britain, the early 19th century also saw the beginnings of conservation efforts. As industrialisation spread, some thinkers and artists, including botanists like Mary Parker, Countess of Macclesfield, worked to document and preserve the country’s native flora. Her botanical sketches highlighted an understanding that nature’s resources weren’t endless, and her work serves as a reminder of the importance of protecting natural habitats against the relentless advance of industry.

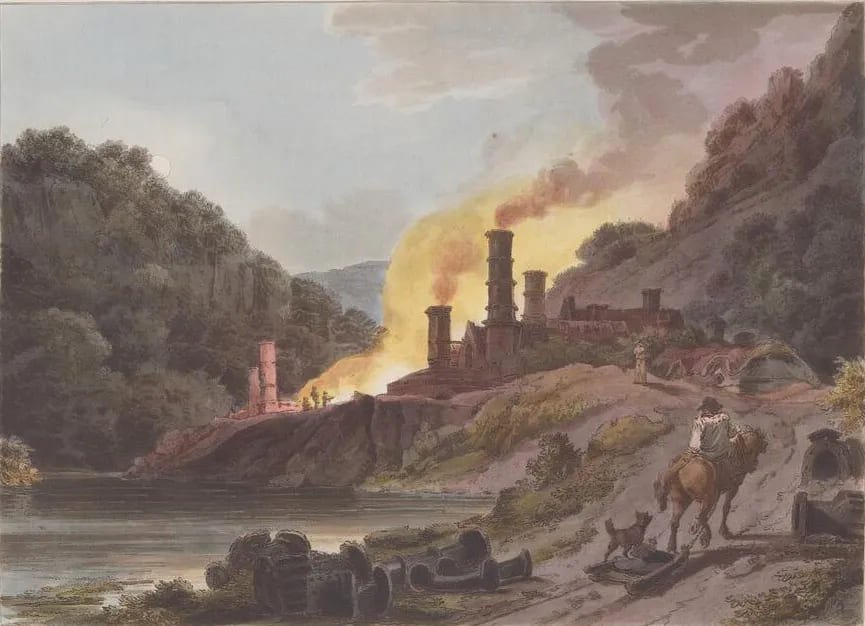

Yet even as voices called for preservation, others celebrated industry as a triumph. Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg’s Iron Works of Coalbrookdale (1805) epitomised this perspective, depicting the fiery heart of industrial Britain with a sense of awe and grandeur. The Iron Works became a symbol of Britain’s transformation into an industrial powerhouse, yet it also foreshadowed the environmental costs of such progress. This tension between admiration for human achievement and concern for its ecological toll is a theme that continues to shape our environmental awareness today.

The Role of Colonialism in Climate Impact

The climate crisis was not only a byproduct of industrialisation but was also entwined with Britain’s colonial expansion. British industry relied on raw materials from around the world, extracted from colonies with little regard for their environmental impacts. The Caribbean, for example, faced widespread deforestation and soil depletion due to sugar plantations, a result of Britain’s colonial appetite. This exploitation of natural resources laid the groundwork for global environmental degradation, tying Britain’s industrial growth to an extractive approach that fuelled the climate crisis.

Art as Advocacy: A British Legacy

Throughout the 19th century, art continued to play a crucial role in shaping public perception of environmental change. The “picturesque” and “sublime” styles of British landscape painting were not merely aesthetic movements; they also served as subtle critiques of the changing countryside. Artists used these techniques to both celebrate and mourn the landscapes threatened by industry. Paintings capturing untouched valleys and rugged coasts became more than depictions of beauty—they were calls to protect a vanishing Britain.

This artistic legacy of depicting nature as both powerful and fragile continues to influence British environmental consciousness. Figures like Henry David Thoreau and William Wordsworth embraced nature as a refuge from the pressures of modern life, offering a counter-narrative to the unstoppable march of industrialisation. Their work inspired the Romantic movement’s appreciation for wild landscapes, a sentiment that eventually spurred the conservation efforts we recognise today.

A Legacy of Environmental Awareness

Today, we face a climate crisis that is both global and deeply personal. The origins of this crisis, as depicted by British artists, scientists, and writers over two centuries ago, provide an invaluable perspective on our current challenges. Their observations remind us that the warnings were there from the start, expressed through paintings, poetry, and scientific studies that documented the first clouds of change.

The ongoing exhibition “Storm Cloud” at the Huntington Library in California briefly acknowledges these British voices, linking them to our present climate discourse.

For more on Britain’s environmental history and insights into today’s climate challenges, follow EyeOnLondon for a fresh perspective on our shared heritage.